April 25, 2024

Climate change is driving the need for new approaches to mapping floodplains and understanding flooding risks

Climate change is causing an increasing number of dangerous and expensive floods across the U.S. — and actions on climate resilience are lagging far behind the pace of change. That's a central message of the Fifth National Climate Assessment, the most comprehensive interagency analysis yet of how climate change will affect the nation in the years to come.

Federal Emergency Management Agency floodplain maps play a crucial role in evaluating the susceptibility of various regions to flooding related to climate change and guiding the work of city planners, real estate developers, and insurance companies. However, many FEMA maps are decades old and don't account for the repercussions of climate change on infrastructure. They are also based on broader, generalized data that may not represent local conditions accurately. Given the regional nature of climate-related hazards, the need for precise mapping and detailed flood risk assessments has escalated in significance.

It's critical that communities, real estate developers, and insurance companies conduct thorough investigations of flood-prone areas, with particular attention to regional data and trends, before designing or constructing new buildings or issuing insurance and setting rates. FEMA flood maps can and should be used during these investigations, but they're only one part of the overall picture.

While federal maps can serve as tools to communicate risk, they frequently suffer from incompleteness or obsolescence, especially in the context of a changing climate.

FEMA floodplain maps rely on historical data

FEMA's flood maps show where the minimum floodplain management regulations, for example, building and land use codes, must be applied. The Special Flood Hazard Areas (SFHAs) defined by FEMA have a 1% chance of being inundated in any given year, i.e., those areas that will be affected by a "100-year flood." Properties within those zones are subject to more stringent building codes and regulations.

Since the inception of the National Flood Mapping Program in 1967, only about one-third of the nation's streams, rivers, and coastlines have been mapped by FEMA, and only one-quarter of these models have been updated in the past five years. Numerous communities throughout the U.S. haven't been mapped for decades, and some of the most outdated maps reflect the nation's most flood-prone areas.

For instance, the FEMA flood map for Calais, Vermont, which experienced a flood exceeding 100-year flood levels in July 2023, was last updated in March 2013. In certain regions of northern Wisconsin, where significant events like 500-year rainfall incidents have occurred multiple times within a few years (July 2016 and June 2018), FEMA maps date back to 1988 and 1978, respectively.

FEMA's traditional floodplain modeling methods depend heavily on historical data and implicitly assume that future hydrologic conditions will occur with the same frequency as past conditions. They reflect previous topography, rainfall, and development conditions, rather than proactively accounting for present or future conditions.

This approach comes with the risk of designing and constructing buildings and infrastructure under outdated conditions, ultimately heightening the vulnerability of these structures to flooding. Additionally, many communities manage flood risks through dams and floodways, which influence how flood waters flow and which may not be captured in FEMA maps.

Special challenges for floodplain mapping in urban areas

Urban areas may pose specific, pressing risks. FEMA floodplain maps primarily focus on capturing river and coastal flooding, while often overlooking the inundation caused by intense bursts of rainfall, referred to as pluvial flooding. This is a concern for cities where many permeable surfaces have been replaced with impermeable ones, like concrete and tarmac.

FEMA floodplain maps are also not well-suited to account for urban stormwater flooding triggered by heavy rainfall and flash floods, which are becoming more frequent and severe. FEMA reports that 40% of claims filed through its National Flood Insurance Program come from individuals residing outside the boundaries of the 100-year floodplain in urban areas, meaning in areas that were not previously considered at risk. FEMA currently categorizes substantial portions of these regions as having a flooding probability of less than once every 500 years.

Failing to account for the effects of climate change

FEMA has proposed regulatory amendments to implement the Federal Flood Risk Management Standard (FFRMS) and revamp the agency's eight-step decision-making process for floodplain reviews, as detailed on federalregister.gov. Under FFRMS, federally funded projects would be required to include margins of safety for flood protection or use future climate projections to inform siting and design decisions, e.g., a climate-informed science approach (CISA). This can help minimize the likelihood of flooding during a project's entire design life.

However, until those updates are made, reliance on FEMA maps to plan for the effects of climate change poses serious risks to infrastructure and people. Hurricane Harvey's impact on the Gulf Coast of Texas in 2017 provides an illustrative example. The Harris County Flood Control District, encompassing the city of Houston, discovered that 50% of the 204,000 homes affected by flooding were situated outside the federal hazard zone as defined by FEMA. While Hurricane Harvey was a 500-to-1,000-year event, these types of extreme climate events are becoming more common.

States and local governments are also behind when it comes to planning for the effects of climate change. Many states and cities aren't yet adopting building or zoning codes that consider how sea-level rise or flooding will affect future development. Just 35% of states and local governments have adopted building codes that incorporate basic flood resilience features, according to FEMA.

While federal maps can serve as tools to communicate risk, they frequently suffer from incompleteness or obsolescence, especially in the context of a changing climate. In cases of map inaccuracies, the minimum building codes may only be enforced within an area smaller than the actual 100-year floodplain, potentially exposing new construction to increased vulnerability.

Trends in independent flood studies

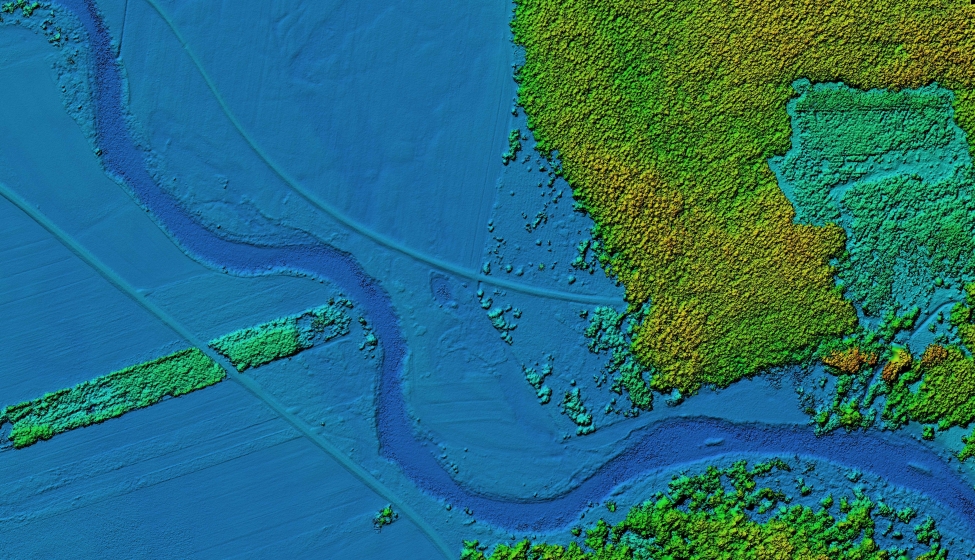

To permit presently low-risk developments in areas where climate change may heighten flood risk in the coming decades, in-depth flood studies can help account for existing and projected climate change. Several states and municipalities have taken proactive measures in creating their own flood mapping initiatives, as a means of developing a better picture of their flood hazard boundaries.

For instance, Mecklenburg County and the city of Charlotte in North Carolina have been incorporating both current and future floodplains into their maps since 2000. Additionally, the Harris County Flood Control District has collaborated with FEMA to update its maps, with the forthcoming release being the nation's first to include considerations for urban stormwater flooding.

Another approach involves the creation of "river corridor" maps to determine flood pathways. These maps account for the fact that rivers change vertically and horizontally over time. While these river corridor maps may overlap with federal flood zones in some cases, they often encompass larger areas. In some towns and at the state level, these river corridor maps have been adopted into zoning regulations. Consequently, when planning construction and setting building standards, these river corridors must be considered — although they may not be as widely recognized or integrated into policies as FEMA maps.

Updated flood maps can also offer a more accurate representation of a building or property's vulnerability to flooding. Various factors influence the 100-year flood event boundary. New construction, community development, or natural phenomena like shifts in weather patterns and terrain can cause changes in water flow and drainage patterns.

Tips for creating in-depth floodplain studies

It's important to address several key questions when reviewing floodplain maps and conducting studies:

- What insights can be gained from current FEMA floodplain maps and associated studies, e.g., FEMA insurance studies?

- Did FEMA's maps and methodologies accurately reflect current conditions?

- What distinctions arise when assessing the role of land subsidence in floodplain delineation (changes in topography)?

- How do alterations in watersheds, such as development and subsidence, influence floodplain boundaries?

- What are the relevant takeaways from the impact of climate change on FEMA floodplain maps and the methodologies employed?

- What methodologies can be employed to evaluate the impact of climate change on FEMA's floodplain maps and assess flood risk?

An in-depth floodplain study can provide a more precise assessment of flood risk tailored to the context of specific development locations and rate zones. An in-depth study also equips stakeholders with more reliable data for long-term planning, empowering informed decision-making for site selection, construction, and investment, which are crucial for sustainability and resilience in the face of evolving flood risks and climate change.

What Can We Help You Solve?

Exponent's multidisciplinary earth science and water resource engineers assist clients in developing floodplain models to more accurately assess the impacts of hydro-climate changes on existing and planned infrastructure. We also help review and comment on proposed state and federal manuals, flood hazard assessments, and strategies to adapt to climate change.

Hydrology & Hydraulics

Identify and address hazards and plan for appropriate water supply with expert analyses and water consulting services.

Asset Management for Extreme Weather Risks

Infrastructure evaluations and analysis to quantify risk and support informed decisions regarding maintenance and power shutoffs.

Sustainability & Climate Change

Scientific and engineering insights to improve and quantify sustainability practices and secure vital resources and assets.

![[EECS] Electrical Risk Management - Hazard Analysis - two workers - Damage Assessment Electrical Power Station Analysis Engineer](/sites/default/files/styles/cards_home_card/public/media/images/Damage-Assessment-Electrical_0.png?itok=BDDSEqPB)

Damage Assessment

Rapid response assessment and remediation recommendations for damaged electrical power lines and distribution systems.

Water Sciences & Management

Sophisticated water consulting services, helping clients adapt to climate change and sustainability challenges.

Hydroelectric Power

Harness hydroelectric power to support a successful sustainable energy transition strategy