January 11, 2023

A series of extreme storm systems has brought record rainfall, severe flooding & landslides to parts of Washington, Oregon & California

Since Tuesday, Dec. 27, a series of "atmospheric river" events has brought heavy rainfall and high winds to the U.S. West Coast, from Washington state to central California. These events have caused widespread power outages, landslides, flooding, storm surge damage, and at least 12 reported fatalities since Dec. 30. As of the date of this alert, another atmospheric river event is currently affecting Northern California with a second system forecast to form over the Pacific this week and further storms reaching California in the second part of January.

It is too early to know the total toll of these events, but damage to infrastructure so far includes levee failures, roadway damage, shoreline infrastructure failures, and construction disruption and delays. Areas of concern include the Santa Cruz mountains, the Sierras, Central Valley levees, and areas affected by recent wildfires. Wildfire-affected areas are particularly vulnerable and pose major ecological, hydrological, and geological hazards to communities and businesses.

Atmospheric rivers

The term atmospheric river refers to long (~1,000 miles) and narrow (~100-300 miles wide) bands of moist air and strong surface-level winds that commonly accompany the migrating front of extratropical cyclones (i.e., storms outside of the tropics). The analogy to a river is fitting, not only because of the thin, meandering appearance of these cloudy plumes in satellite imagery, but also because of the remarkable quantities of water these systems carry. During the peak intensity of their short lifecycle (typically ~3-5 days), atmospheric rivers can transport water at volumetric flow rates comparable to the Amazon.

Californians are no strangers to atmospheric rivers. West coast winter storms are frequently associated with a westerly flow of moist air that originates in the vicinity of Hawaii and brings concentrated rainfall to the California coast. This recurring phenomenon is so common that such events have become informally known as "Pineapple Express" storms. However, the systems affecting Northern California since Dec. 27 have been particularly intense, and the interval between storms has been exceptionally short. With more rainfall in the forecast for this week and later this month, the number of successive storms is also abnormally high.

Storm systems so far

The first system in the current string of atmospheric river events brought approximately 2-4 inches of rain to the San Francisco Bay Area and surrounding Coast Range mountains over 24 hours. The National Weather Service's Portland office recorded wind gusts up to 86 miles per hour on the Oregon coast (above the level of a Category 1 hurricane).

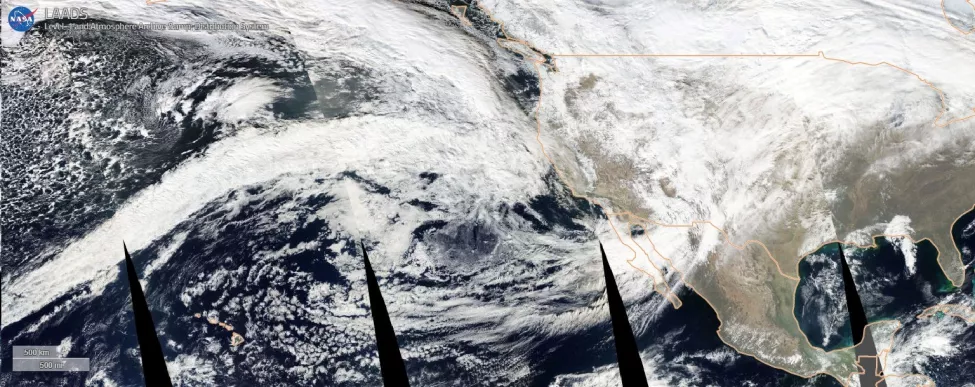

An even wetter system hit the region four days later between Dec. 30 and 31 (Figure 1), bringing with it San Francisco's second highest 24-hour rainfall total in over 170 years (5.46 inches, or less than one-eighth of an inch shy of the record). With heavy rain falling on already-saturated soil, the San Francisco Bay Area, Santa Cruz, Sacramento, and the Sierra foothills experienced widespread flooding and landslides. Highway 101 and Highway 50 were blocked by flooding, and State Route 271, State Route 299, and Highway 70 were reportedly blocked by landslides.

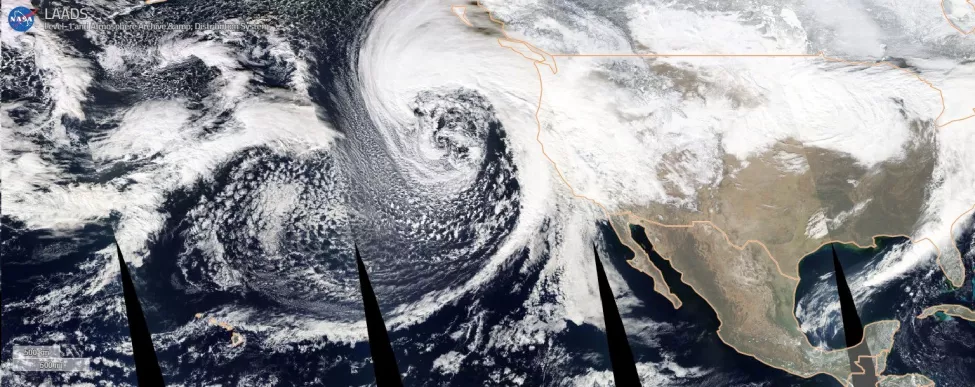

The new year saw a short break in the weather until Jan. 4, when a "bomb cyclone" (defined as a rapidly intensifying storm where the pressure drops faster than 1 millibar per hour) off the coast of Northern California brought the third atmospheric river to the area in just over a week (Figure 2). California Governor Gavin Newsom declared a state of emergency, and several communities issued evacuation orders. The Jan. 4 system brought less rain but higher winds than the Dec. 31 storm, with damage reported across the region, including tens of thousands without power and the partial collapse of the Capitola Wharf in Santa Cruz.

The next storm systems

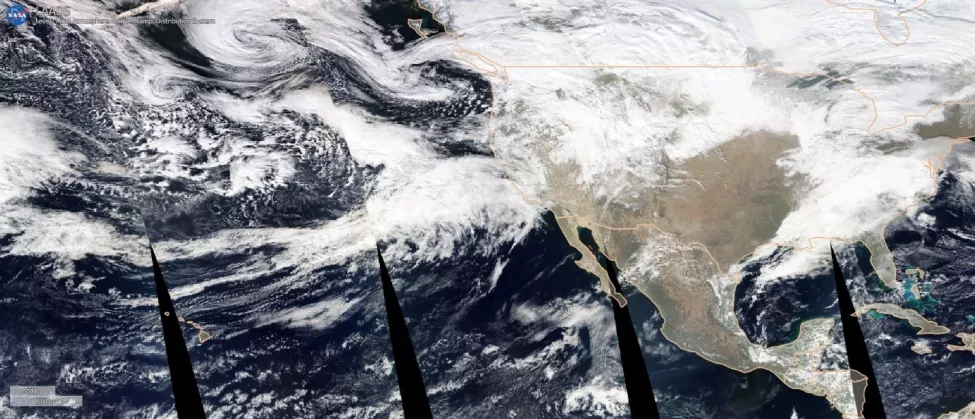

As of the date of this alert, another atmospheric river event is currently affecting California (Figure 3), with the National Weather Service forecasting the heaviest rain and strongest wind already affecting the coastal areas and continuing into the afternoon and evening of Tuesday Jan. 10. A large swath of the state will be affected by this system, with 90% of Californians currently under flood watches and advisories by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Increasing landslide potential

With even more rain predicted through the end of the month there will almost certainly be further damage. Mountainous population centers such as Santa Cruz and the Sierra Foothills are at particular risk due to steep landslide-prone topography and the elevated levels of rain induced when moisture-laden air is forced upward by the terrain, causing the entrained water vapor to cool and condense as precipitation. Many areas in the mountains have also been burned by wildfires in recent years, significantly increasing debris-flow hazard.

Debris flows are a type of slope failure often trigged by storms. Debris flows are rapidly moving mixtures of soil, rocks, debris (like uprooted trees, bushes, fences, etc.), and water. Areas burned by wildfires are especially susceptible to debris flows, erosion, and excessive sediment production (even if the wildfire occurred years ago), as the burnt soil and loss of vegetation limit surface water infiltration and provide loose, easily mobilized material during heavy rains. Debris flows in burned areas can travel miles and affect places that were not burned.

The West Coast is well known to be susceptible to landslides, which can range from small erosional features to larger, deep-seated landslides that can move entire neighborhoods downslope. Deep-seated landslides can lay dormant for long periods until trigged by rainfall, particularly after prolonged above-average rainfall periods. With these conditions becoming increasingly likely due to current storm systems impacting the West Coast, the potential for significant landslides increases with each successive atmospheric river impacting the area.

Impacts on infrastructure

California's vast water infrastructure is also at-risk during times of heavy rain, as in the 2017 Oroville Dam crisis. California's dam and Central Valley levee system is of vital importance to the state, as it protects the region's fresh water from mixing with the saline seawater of San Francisco Bay and provides potable and irrigable freshwater to most California residents. The levee system in the California Central Valley will be tested by rapidly rising water levels, which could lead to overtopping and other levee failures, like the breaches that have occurred near Wilton, California, in Sacramento County during this recent series of storms.

These levee failures, landslides, and damaged or overwhelmed stormwater conveyance systems have also resulted in significant flooding of roadways, buildings, and other infrastructure.

How Exponent Can Help

Exponent is well qualified to assist clients affected by such extreme weather events. Exponent staff have deep industry and research experience assessing all aspects of storm-related damage including landslides, erosion/scour, flood-related health hazards, and damage to earth structures (levees, dams, retaining walls, foundations), buildings, and infrastructure.