June 3, 2025

A look at the environmental impacts of seabed mining in the face of shifting and in-progress policies

In April, the California-based deep-sea mining company Impossible Metals asked the U.S. government to grant it access to nearly 30,000 square miles of seabed off the coast of American Samoa in an area known as the Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone (CCZ). Later that month, President Trump issued an Executive Order announcing his intent to open U.S. waters to seabed mining. Five days later, Canadian deep-sea mining company The Metals Company asked the U.S. administration to approve plans to mine the international seabed.

All parties, including the current U.S. administration, are interested in collecting polymetallic nodules off the sea floor in areas like the CCZ, which holds the most well-studied deposit of polymetallic nodules on the planet. These baseball-sized rocks contain many minerals, including manganese, iron, nickel, titanium, molybdenum, and cobalt — minerals critical to lithium-ion battery production. Studies on the potential environmental impacts of seabed mining, however, are evolving, and there currently are no regulations to address its possible effects. As a result, the rush to mine the sea floor may expose companies and governments to legal action related to potential damage to the biosphere.

Regulatory landscape for seabed mining

Currently, any country can allow deep-sea mining in its own territorial waters up to 200 nautical miles from shore, known as that country's exclusive economic zone (EEZ). Beyond those boundaries, the International Seabed Authority (ISA) acts as the intergovernmental body in charge of undersea mining. Formed under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), ISA's mission is to "ensure the effective protection of the marine environment from harmful effects that may arise from deep-seabed-related activities."

While the U.S. has participated in several ISA conventions, it has not signed the treaty, and attempts to ratify it have been blocked in the U.S. government. ISA has been working on regulations for seabed mining since 2014, but none have been finalized. At present, the agency forbids any seabed mining in international waters, leaving potential proposals in limbo.

Environmental concerns over seabed mining

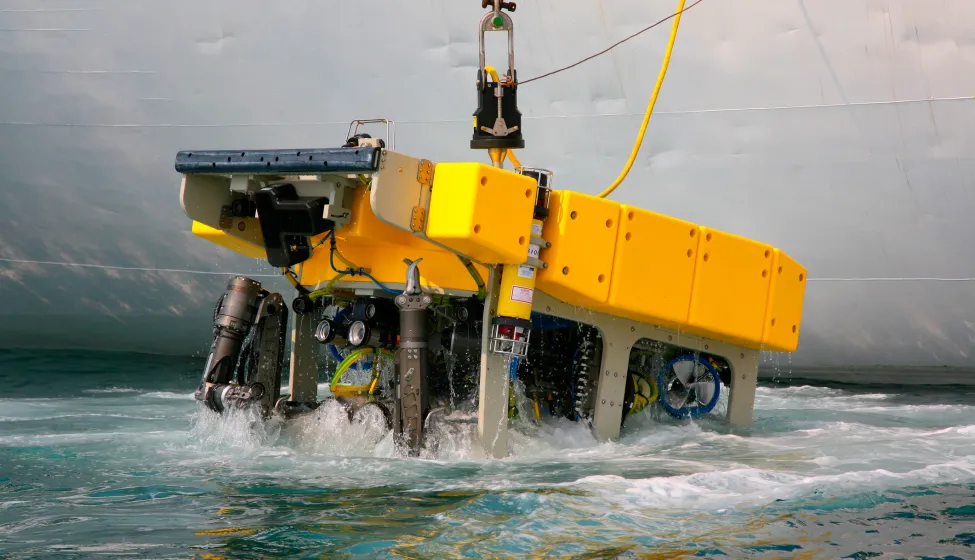

UNCLOS member nations have called for a moratorium on seabed mining, citing potentially dire environmental consequences. In 1979, Ocean Minerals Company conducted a seabed mining test in the CCZ, collecting polymetallic nodules off the seafloor with a 10-meter wide, self-propelled remotely operated mining vehicle connected by a riser pipe and pump system to a surface ship. The test disturbed approximately 0.4 square kilometers of ocean floor, an area about the size of the Mall of America and larger than what was mined.

More than 40 years later, researchers from Britan's National Oceanography Centre returned to the site of the test to assess its environmental damage. Their study of the area, published in Nature in 2025, found that long-term sediment changes reduced the populations of many larger organisms living on the seabed while some smaller creatures recovered. Overall, the researchers state in their paper that the environmental consequences of seabed mining could be dire:

"The expected high sensitivity of abyssal communities to change combined with the potential spatial and temporal scales of mining operations … sets them apart from most other anthropogenic stressors in the deep sea. Nodule mining is expected to cause immediate effects on the seabed surface and habitat in the path of collector vehicles, including mechanical disturbance, hard substratum habitat removal and sediment compaction. It will generate sediment plumes in the water column that can redeposit beyond mined areas causing biogeochemical alterations of the sediment and increased water turbidity at scales that could have significant impacts on ecosystems."

Another paper by international researchers also found that the CCZ contains up to 30 cetacean species (whales and dolphins) that could be disturbed by seabed mining operations.

What's next for seabed mining?

Any organization considering seabed mining can actively track ISA for potential developments in international mining, in addition to fully researching national laws for EEZ mining. One likely requirement for any seabed mining activity will be rigorous environmental impact reports for government agencies and environmental groups. While the global approach to seabed mining remains in flux, navigating the contrasting and even contradictory regulatory schemes that are now taking shape will require detailed understanding of national and international legal and environmental compliance issues.

What Can We Help You Solve?

Exponent's environmental scientists can conduct detailed environmental impact analysis of any seabed mining or other exploratory undersea efforts. Our experts have worked with national and international lawmakers for decades to help ensure that mining projects meet environmental standards and public expectations.

Environmental & Regulatory Compliance

Rigorous analyses to help clients overcome complex environmental and regulatory hurdles and meet auditing obligations.

Environmental Risk Management

A proactive approach to environmental risk management, including past and current facility processes and chemical releases.

Environmental Costs & Liabilities Consulting

Accurately determine present and future environmental costs, liabilities, and apportionment.

![[EBS] Ecological & Biological Sciences - Environmental Risk Assessment - grey heron grazing in fresh water](/sites/default/files/styles/cards_home_card/public/media/images/grey-heron-2022-01-04-23-54-37-utc%281%29_0.jpg.webp?itok=5EB0lXjA)

Environmental Risk Assessment

Risk assessments for legacy spills and contamination, potential project and product impacts, and environmental remediation support.

Environment & Sustainability

Actionable, science-based assessments and expert consulting to help companies understand and mitigate their impact on the environment.

Environmental Engineering

Objective evaluation to help prioritize resources for cost-effective, compliant environmental remediation.